How Progress is Made - Part 1

This article is long ( ~ 1h read), so I have split it into three parts of ~ 20 minutes each.

- Part 1: Introduction, Definition of Progress, Episodic vs Continuous Tasks

- Part 2: Progress by search, structure of search spaces, why induction works

- Part 3: The role of predictive models, infrastructure and competition (coming soon)

Introduction, Definition of Progress, Episodic vs Continuous Tasks

A few weeks ago, I was lying in the couch with my girlfriend doing some pre-sleep binge-watching of YouTube videos. We were about to go to sleep when a wild 45 minutes video titled The History of Wii Sports World Records from the channel Summoning Salt appeared in my recommendations. I decided to give it a go. My girlfriend of course fell asleep, but I stayed up late, mesmerized by the most boring topic I could imagine: a documentary about the history of Wii Sports speedrunning. I didn’t even know that you could speedrun Wii Sports (lol). You don’t need to watch his videos to understand this article, of course, but I believe if you check them out, you’ll get a clearer picture of what I’ll try to convey in this article.

A speedrun is a play-through of a video game with the intention of finishing the game it as fast as possible. Speedruns are usually performed in games that have a clear end goal, like defeating the final boss or completing all the levels. It’s generally a well defined task with a clear metric to measure progress: time.

The videos of Summoning Salt follow always a similar structure:

He starts by introducing the game and the rules for the speedrun.

He then goes through the history of the speedrun, starting from the first world record and going through all the different developments that lead to the current world record: new strategies, improvements in execution, etc.

I think these videos offer a exceptional global picture of how “how progress happens” for a complex task in a global environment with multiple optimizing agents. Why is this relevant? Well, now we are starting to see the birth of systems that have a non-trivial level of generality and agency. Usually, discussions around optimization and search focus mainly on specific tools and algorithms but a global perspective that discusses the interplay of various elements and factors is rarely explored. My goal in this article is to present a a global perspective of how progress happens with the hope that it can be exploited to accelerate progress in targeted domains, similar to how the results of game theory can be used to design system rules that incentivize certain outcomes.

Some elements of progress

Let’s start by taking a look to speedrunning and identify some of the elements that contribute to progress there, which I believe are common to progress in general.

Exploration of the search space: The search space is the set of all possible solutions to a problem. In speedrunning, the search space is the set of all possible ways to complete the game. For most games, this is practically an infinite set. How do players explore this space? How do they find new ways of completing the game with a better time? How do they construct these complicated strategies that only work when executed in perfect synchronization? It’s obviously more than just random trial and error.

Generally intelligent agents: when you program a Reinforcement Learning agent, you usually start with a blank slate: a function with random parameters that is refined using rewards signals to tweak these parameters. In contrast, speedrunners aren’t simply an array of random values reacting to numeric scores. They’re humans with pre-existing knowledge about the world and video games. This information is stored sparsely in the neural networks that make up their nervous systems that is a product of mainly two factors: an evolutionary process that has shaped the human brain over millions of years, and the influence of the environment during their lifetime. These neural systems can generalize from this information and construct a model of the game to make predictions about the consequences of their actions. This way, they design strategies that exploit the game’s mechanics to their advantage. And these models are updated by new experiences, either from their own play-throughs, from watching other speedrunners, or from any other source of information they acquire through their senses. Several questions arise:

- How they transform their prior knowledge into a model of the game? And why does it work?

- How do they use this model to construct strategies?

- How do they update this model with experience?

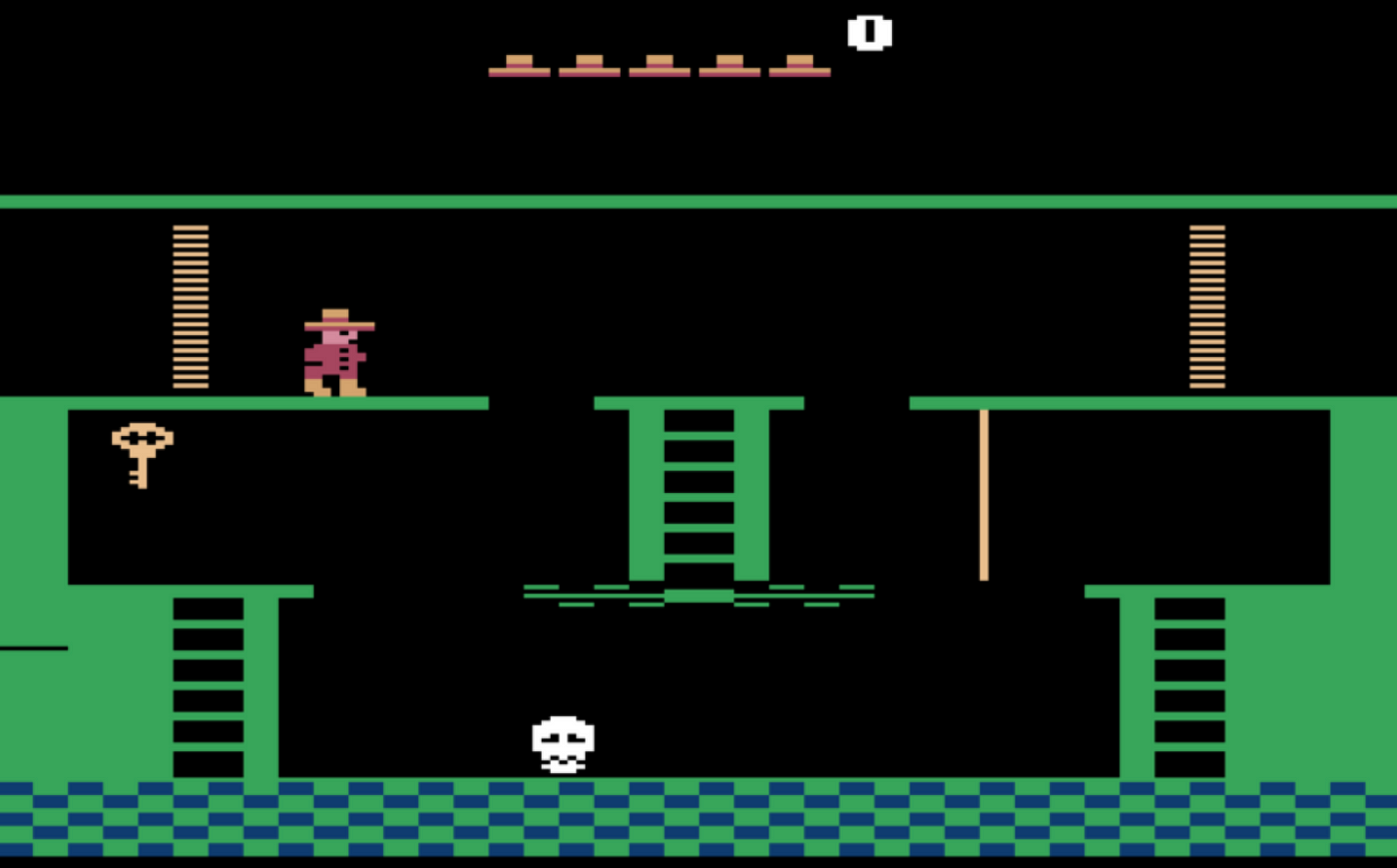

An example of generalization is the following. In the classic videogame Montezuma’s Revenge there are some pixels representing ladders. If you give this game to a 7 year old kid from the 80s that never played a video game before, he will probably identify that you can use the ladders to go between levels before even trying to use them. This is because he has seen ladders in real life, he identifies the similarities with the pixels in the game, and he performs an inductive inference associating the properties of the real life ladders to the game ladders. And this inference works because the developers of the game happen to live in the same world as the kid and share a common understanding of what a ladder is and how it’s typically used. On the other hand, a vanilla RL agent can’t possibly infer the properties of the ladder from the pixels without exploration, since it doesn’t have any pre-existing knowledge to generalize from.

- Competition among optimizing agents: Speedrunners generally compete among themselves to get the best time. Speedrunners usually try to improve until they reach the world record. Once they reach it, they usually (but not always) stop playing the game. The incentive is mostly honor and recognition, which sometimes is linked to monetary rewards in the form of donations or sponsorships. This competition plays a non-trivial role in accelerating progress.

- Why do speedrunners compete?

- How does competing help them get better?

Communication and collaboration: Speedrunners must provide a video of their play-through to validate their records. The community then reviews this video to confirm the record’s legitimacy. This process is essential for accelerating progress. By requiring speedrunners to share their strategies in detail for verification, it enables other speedrunners to learn and build upon this knowledge. This level of openness isn’t always present in other fields, such as when private companies withhold specific details about their technology (e.g., OpenAI not disclosing the details behind GPT-4). Why does this communication contribute to progress?

Refinement: Speedrunners spend a lot of time refining their skills. They practice specific parts of the game over and over again until they master them. They essentially fine-tune their motor skills to perfection. This is a meta-optimization process that happens on top of the optimization process of finding the best strategy. How does the nervous system adapt to improve the execution of a strategy? Is this process similar to the process of finding a strategy?

- Tools and infrastructure: Speedrunners use and develop tools to help them improve their performance. For example, they use software to record their play-throughs and analyze them frame by frame to identify mistakes and areas of improvement. They also use software to analyze the game’s code to find glitches and exploits. This cumulative process of developing tools and infrastructure is essential for progress, since it allows agents to explore the search space more efficiently.

I think these elements are common to progress in general. For example, in science, we have the exploration of the search space (experimentation), the use of generally intelligent agents (scientists), competition among optimizing agents (fight for funding and recognition), the communication and collaboration (publication and peer review), the refinement of skills (education and training), and the development of tools and infrastructure (computers, measuring instruments, etc.).

In the next sections, I’ll try to formalize these ideas and hopefully at the end of the article, we’ll have a better understanding of how these elements interact to produce progress.

Definiton of progress

Progress must always be defined in relation to a specific task, coupled with a metric we aim to optimize. For example, in speedrunning, progress occurs whenever a new world record is set. Without a quantifiable pair of goal and metric, progress becomes little more than a buzzword. Politicians often exploit this term, leaning on its shared meaning among us, even though the goals and metrics each of us optimizes for may vary significantly from one another—and likely from what a political party might consider as progress. Whenever you hear the word progress you must ask yourself: progress towards what?.

Said more formally, progress constitutes an improvement in performance for a specific optimization task. Many might argue that this definition of progress is somewhat unconventional. Conventionally, progress is perceived as the act of reducing the distance—in some metric space over the configuration space of a system—between a system’s current configuration and a desired one. In simpler words: if you are in a race, you progress if you move closer to the finish line. However, this is just a special case of an optimization task, aiming to minimize the distance to the goal. In many cases, the goal is not bounded (e.g. the goal of increasing life expectancy in a society) so the optimization frame is more appropriate. But essentially, it’s the same thing.

Episodic vs continuous tasks

Once we agree on what we mean by progress, we need to define what we mean by optimization tasks. In general, there are two types of optimization tasks: episodic and continuous.

Episodic tasks

These tasks deal with systems that can be reset to an initial configuration. In these cases, an strategy $s\in S$ is applied to solve a task $T$, and the performance metric $M_T : S \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ is measured at the end of the episode to estimate the performance of $s$ in $T$. For an episodic task, progress occurs when we find a new strategy $s_{i} \in S$ that improves the performance metric over all the previously known strategies $s_{j} \in S_{\text{known}} \subset S$. Here, $S$ is the set of all possible strategies (which might or might not be infinite).

In general, there’s not a one-to-one correspondence between a strategy and the performance metric. In most cases, the performance is a probabilistic function of the strategy. For example, a deterministic strategy for playing Blackjack (e.g., ask for a card if the sum of the cards is less than 17) won’t always yield the same result due to the randomness introduced by the shuffling of the deck. So, it’s better to talk about the expected performance of a strategy. In the case of Blackjack, we can define the expected performance as the average amount of money we win or lose over a large number of games played with the same strategy. So, to be general, we should say that progress occurs when we find a new strategy $s_{i} \in S$ that improves the expected performance metric over all the previously known strategies. Nonetheless, we can always, redefine the performance metric to be the expected value of the metric for a given strategy, this is $M_T^{\text{det.}}(s) = \mathbb{E}[M_T]_{s}$, and therefore keep dealing with deterministic metrics.

Examples of episodic tasks

Let’s look at some varied examples of episodic tasks to get a better understanding of the framework I’m trying to construct.

1. Blackjack

- Task: Play Blackjack.

- Strategy: An algorithm that tells us what to do in every possible situation. For example, if we ignore splitting and the nitpicky details of the game, we can define any deterministic strategy as a function $s: \mathbb N \rightarrow \{\text{hit}, \text{stand}\}$, where $\mathbb N$ is the set of all possible sums of cards we can have in our hand. For instance, we can define $s$ so that $s(n < 17) = \text{hit}$ and $s(n \geq 17) = \text{stand}$, where $n$ is the total sum of our cards.

- Performance metric: The expected amount of money we win or lose over a large number of games played with the same strategy $s$. We can define this quantity as $\mathbb E[M]_{s}$, where $M$ is the amount of money we win or lose in a single game (assuming a fixed bet size).

2. Chess

- Task: Play chess against a random pool of opponents.

Strategy: In chess, a strategy can be conceptualized as a Turing machine that accepts the current state of the board as input and produces a legal move as its output. The entire strategy space $S$ is practically infinite due to the many sequences of moves possible. However, in developing models or algorithms to play chess, we choose representations of the strategy space. These representations either cover a smaller, more manageable subset of $S$, making them more tractable from a search perspective (e.g., rule-based strategies or tree search algorithms), or they possess desirable mathematical properties like differentiability (e.g., neural networks) that enable interesting optimization methods like gradient descent.

- Performance metric: An example of a performance metric often used in chess is the Elo rating. The Elo rating system quantifies a player’s/strategies skill level based on their past game outcomes against other players/strategies. The difference in ratings between two players/strategies is intended to serve as a predictor of the expected result of a match. The Elo rating of a strategy can be determined after a long series of games against a random pool of opponents that is assumed to be constant. It’s worth noting, however, that in real-life chess, the pool of opponents isn’t static; it evolves over time as new strategies emerge and newer engines are developed. In that case, the problem ceases to be episodic and becomes continuous.

In the context of chess, one can envision a human player as a computer that processes the scattered photons from the board to reconstruct the state of the board, and through a series of synaptic connections and chemical reactions, produces a legal move. In this scenario, the complete molecular configuration of the player’s brain represents the strategy.

Progress in episodic tasks is a search problem

In episodic tasks, progress is achieved by finding a new strategy that improves the performance metric over all the previously known strategies. In other words, progress is achieved by searching for a better strategy. So talking about progress, optimization, and search in episodic tasks is essentially the same thing.

- What are we dealing with?

- We have a big set of strategies, which we’ll call $S$.

- Each strategy has a performance score, given by $M_T(s)$.

- What’s our goal?

- We want to find the best strategy, $s^*$, which has the highest score. Mathematically, this is: \(s^* = \arg\max_{s \in S} M_T(s)\)

- What’s the challenge?

- We don’t know the scores for all strategies upfront. We have to test or calculate the performance of each strategy.

- This strategy set, $S$, can be very large, oftentimes infinite, making it impractical to check every single strategy.

- How do we search?

- In general, it depends on the task, the structure of $S$ and the resources available. In the Part 2 of this article, I discuss this topic in more detail.

Continuous tasks

Continuous tasks involve systems that cannot be reset to an initial configuration. In these tasks, the system evolves uninterruptedly over time, and actions taken can influence future states and outcomes. This poses a challenge when defining progress, since the definition of progress in episodic tasks is not applicable since we can’t reset the environment to an equivalent state to compare strategies.

Actions over strategies

While a continuous task could technically be framed as a single episode of an episodic task, this viewpoint is not particularly insightful. In continuous tasks, it is more useful to consider strategies as evolving processes that adapt over time depending on the dynamical evolution of the system. Instead of deploying an entire strategy at once, we execute a sequence of actions $a \in A$, with each action affecting the future state of the system. In this context, a policy $\pi$ is a rule or set of rules that determines the appropriate action $a$ at each time step $t$. Thus, our policy $\pi : X \rightarrow A$ is a function mapping the system’s state $x_t \in X$ to actions $a_t \in A$. This mapping may be deterministic or stochastic. The system’s evolution $X$ can vary widely. While it is common to model the system’s evolution $X$ as a Markov process and $\pi$ as a policy within a Markov decision process (MDP), this simplifies the complexity of many real-world systems, which often exhibit non-Markovian dynamics. For instance, societal systems involve humans whose memories affect their decisions. Additionally, observations in dynamic environments are frequently time-correlated, meaning that even if the underlying system is Markovian, the observations may not be (see Hidden Markov models).

Note that we are using the word policy instead of strategy here. We can understand in this context that an strategy is the choice of a policy. I know it’s a bit redundant, and there’s a lot of overlap between the two terms, but I think it’s useful to distinguish between them. In general, I’ll use strategy when talking about episodic tasks and policy when talking about continuous tasks.

Performance metric in continuous tasks

Unlike episodic tasks where performance is measured at the end of an episode, continuous tasks require ongoing optimization, as they do not allow the opportunity to reset and retry. This requires a performance metric that can be evaluated in real-time as the system evolves.

Typically, the performance metric is a function that considers the history of the environment up to the current point in time, denoted mathematically as $R: X^{t} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, where $X^{t}$ is a sequence of states $\{x_0, x_1, \dots, x_t\}$ up to time $t$. The objective is to influence the system’s evolution through actions that bring the performance metric $R$ closer to a target value $R_\text{goal}$. Progress is made when a new measurement of $R$ is closer to $R_\text{goal}$ than the previous measurement.

For example, consider the task of controlling a room’s temperature. We could define the performance metric as the difference between the current temperature $T(t)$ and the desired temperature $T_\text{goal}$, expressed as $R(t) = |T_\text{goal} - T(t)|$. The goal is to achieve $R = 0$, indicating that the current temperature matches the desired temperature. Progress is made whenever $R$ decreases.

However, this simple metric may lead to issues. For example, if the room is 1 degree cooler than $T_\text{goal}$ and the heater is activated, the temperature will rise, which seems like progress. Nonetheless, t’s usual that heating systems have some delay between the activation signal and the power being delivered to the room. So, if the heater is turned off only when the temperature reaches $T_\text{goal}$, the temperature will continue to rise and exceed $T_\text{goal}$, resulting in a deviation in the opposite direction. Ideally, the heater should be turned off before the temperature reaches $T_\text{goal}$ to prevent overshooting. This illustrates a common challenge in continuous optimization tasks: balancing immediate progress with long-term stability. To address this, the performance metric can be refined to include not just the current temperature difference, but also the rate of change and the cumulative error over time. Those familiar with control theory will recognize these as the proportional, integral, and derivative terms in a PID controller.

Examples of continuous tasks

1. Room temperature control

- Task: Maintain the temperature of a room at a desired temperature $T_\text{goal}$.

Policy: A policy $\pi$ might dictate the specific conditions under which a heating or cooling system gets activated. For instance, when the temperature is below a certain threshold, the heater could be turned on, and when it’s above another threshold, the AC might be activated. Such a strategy can be defined as:

if T < T_goal - delta: Turn heater ON if T > T_goal + delta: Turn AC ON else: Do nothingHere,

deltais a small margin around the desired temperature to prevent the system from toggling the AC/heater too frequently.Performance metric: A straightforward performance metric for this task would be the difference between the current room temperature $T(t)$ and the desired temperature $T^*$, expressed as $R(t) = |T_\text{goal} - T(t)|$. However, considering the problems of overshooting and short-term vs long-term optimization, a more sophisticated metric that factors in the rate of temperature change and the past performance (to prevent oscillation) might be appropriate. Such a metric might look like:

\[R(t) = \alpha |T_\text{goal} - T(t)| + \beta \frac{d}{dt} (T_\text{goal} - T(t)) + \gamma \int_{t-\tau}^{t} |T_\text{goal} - T(y)| dy\]where $\alpha$, $\beta$, and $\gamma$ are weighting coefficients, and $\tau$ is a time window over which past performance is considered. We can see that the example strategy above would not perform optimally with this metric, since it doesn’t consider the rate of change or past performance.

2. Portfolio management in the stock market

- Task: Invest in a portfolio of stocks to maximize returns.

Policy: A policy would dictate how to allocate funds among different assets over time. However, crafting a policy for the stock market is complex because is the product of the interplay between countless economic entities shaped by billions of humans. Some rely on inductive reasoning, analyzing historical data for patterns, while others use world models or trust their intuition, essentially a form of brain-based pattern recognition.

- Performance metric: The performance metric is usually the return on investment (ROI) over a given time window. For example, if we invest $1000$ dollars in a portfolio and after a year, we have $1200$, then the ROI is $20\%$. However, this method is not very precise since fluctuations and luck can deceive us when evaluating the performance of a policy. As with the room temperature control, introducing an average of the ROI over the time window (essentially, the integral term) can help us get a more accurate picture of the performance of a policy.

3. Increasing life expectancy in a society

- Task: Enhance the overall health and living conditions of a society to increase life expectancy.

Policy: Policies might encompass various public health initiatives, awareness campaigns, and investment towards the development of medical technology. The strategy space is vast and complex and cannot be defined with a computer program. Usually, institutions in charge of this task summarize ambiguous but directional principles to guide concrete actions that can be implemented by executing agencies. One of the main difficulties of this kind of tasks is that the environment is so complex and non-reproducible that it’s hard to determine the impact of a particular policy. For example, if a government invests in a new hospital, it’s hard to determine how much of the increase in life expectancy is due to the hospital and how much is due to other factors, like the development of new technologies. This is a common problem in continuous tasks.

- Performance metric: the primary metric would be the average life expectancy of the population over a specific time frame. However, life expectancy alone might not give a complete picture of society’s health. Hence, metrics that factor in the quality of life, such as Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) or Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY), would be more indicative. Combining these metrics can offer a more comprehensive understanding of the overall health and well-being of a society.

Progress in continuous tasks can’t be defined as a search problem

In search problems, we assume the ability to independently test different candidate solutions or strategies. This allows valid comparisons between strategies to determine which performs best. We can isolate the effect of each strategy through replication - by resetting the system to its initial conditions and rerunning the same strategies multiple times.

However, in continuous tasks, independent replication is not possible. This makes it impossible to systematically search the policy space or to verify with certainty that a given policy leads to better results independent of other factors. Comparing policies becomes an “apples to oranges” problem since their contexts continually diverge.

Also, it means the performance and outcomes of different policies cannot truly be attributed to the strategies themselves. The effects of a policy are not isolated but rather intertwined with the effects of other policies and the environment itself. This makes it very difficult to attribute a causal relationship between a policy and its outcomes.

Progress in continuous tasks is a prediction + search problem

If progress in continuous tasks cannot be defined as a search problem, how then can we approach it? The key is to obtain predictive models of the system that enable us to estimate the impact of our actions. This allows us to search without actually performing the actions, and thus solve the problem of independent replication.

Some key aspects of progress in continuous tasks are:

We can no longer isolate the effects of individual strategies. Instead, our focus shifts to modeling the response of the system to our actions.

Even though we can’t apply search methods directly, we can still search using the estimated performance of our predictive models.

Performance is evaluated based on how well our actions steer the online optimization process over time.

Progress is made incrementally as our models continuously assimilate new experience to enhance predictive accuracy.

Is not a coincidence that the biggest increase in progress in all areas of human life has happened in the last 300 years, which coincides with the development of the scientific method. The scientific method is essentially a process of building models of the world and using them to make predictions. The more accurate our models, the better our predictions, and the better actions we can take to optimize whatever we’re trying to optimize.

Blurry lines between episodic and continuous tasks

The distinction between episodic and continuous tasks is not always clear.

Sometimes, inherently continuous tasks are framed episodically. This is often done to simplify the problem and make it more tractable. For example, in reinforcement learning, many problems like the Car Pole balancing problem are continuous tasks, but are often framed episodically by limiting the number of steps to a fixed number or assigning a terminal state. This allows to use powerful search methods to find the best strategy, often requiring millions of episodes since the search space large. However, in most situations, this is not a realistic approach. In the real world, we can’t reset the environment and try again. Or if we can, we are constrained by the number of times we can do it.

Conversely, there are situations where episodic tasks demand adaptive strategies. In chaotic environments, even with the capability to reset, outcomes can fluctuate dramatically due to minor variations. Such unpredictability can render search-based methods ineffective. In these situations, predictive models become useful. For example, in the Wii Sports speedrun video that I talked about at the beginning of this post, a player discovered that by removing and then reinserting the batteries of the Wii remote during a golf swing, the game erroneously allows the player to hit on the ball again. Such a glitch could not be exploited through random based search since the chances of concatenating the right sequence of actions by chance are effectively zero. It requires an underlying model of the game’s mechanics that enables to estimate the outcome of unconventional, sequential hypothetical actions. This allowed the player to plan how to use the glitch to bypass obstacles, like a lake, in a way that would be impossible find through episodic search.

Summary of Part 1

Speedrunning offers a fascinating lens through which to study how progress is made: a competitive environment, exploration of vast search spaces, implementation of strategies, refinement of skills, collaboration, communication, and the use of tools and infrastructure.

Progress is defined in relation to a specific task and a metric that is being optimized. A clear goal and metric are essential to prevent the term “progress” from becoming ambiguous or meaningless.

Episodic tasks are those in which the system can be reset to an initial configuration, allowing strategies to be independently tested and compared based on a performance metric. Progress in episodic tasks involves a search for new strategies that outperform the existing ones, and tools like models and heuristics help navigate the large search space of potential strategies.

Continuous tasks do not allow the system to reset, making it challenging to compare different strategies directly or attribute outcomes to specific actions. Progress in continuous tasks thus requires developing predictive models of the system to estimate the impacts of actions and guide decision-making.

The distinction between episodic and continuous tasks is not always clear-cut. Sometimes, continuous tasks are framed episodically for simplification, and vice versa—episodic tasks may be approached with adaptivity when faced with chaotic and complex environments.